This post was originally published in 2019 and updated in 2024

Written by Terrell Huyck

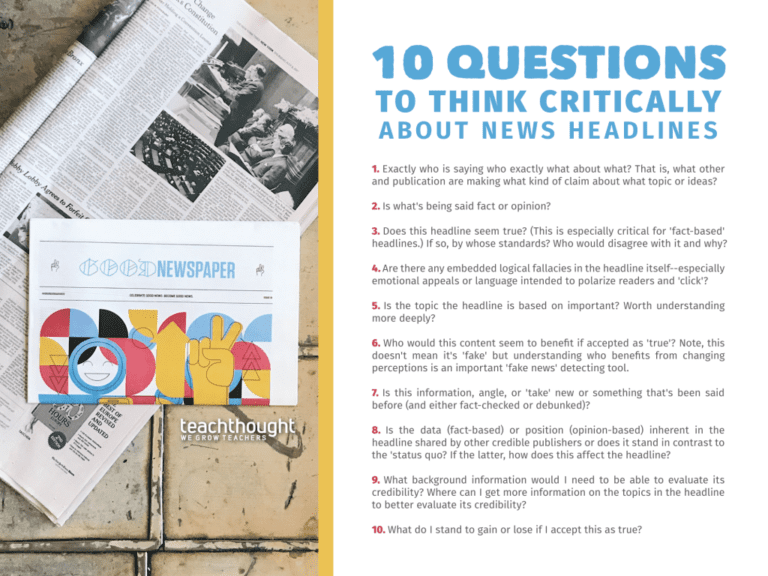

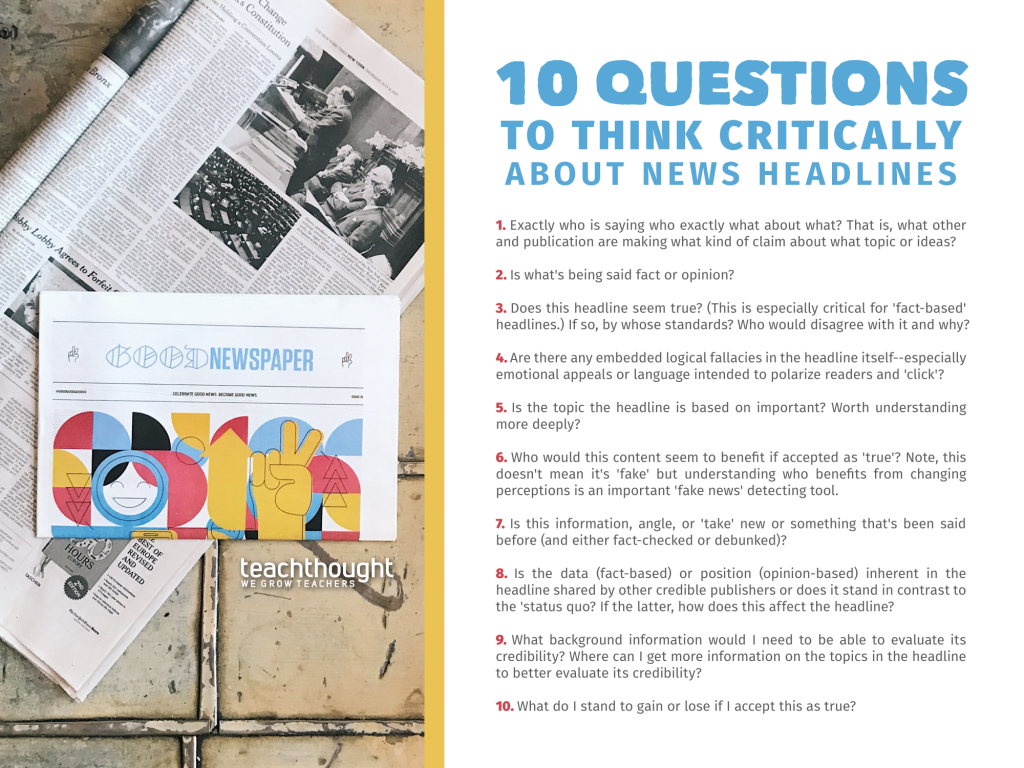

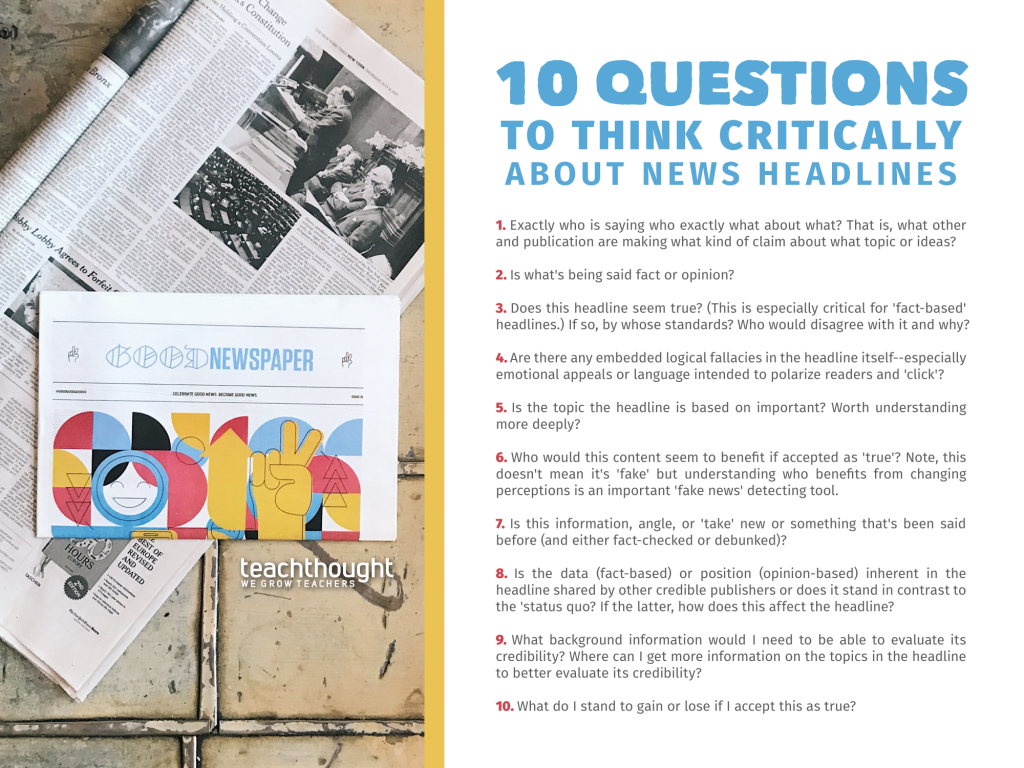

1. Who is saying what in an article, headline, or social share? In other words, what specific authors and publications are making what claims about what themes and ideas?

2. Is what is being stated or asserted fact or opinion?

3. Do you think this headline is true? (This is especially important for “fact-based” headlines.) If so, by whose standards? Who would object to it? ?And what is the reason? How can I check the facts? The author uses the “gray area” of “truth” in a way that is intended to sway the reader’s opinion, raise questions, influence thinking, or otherwise change the reader’s opinion. Have you not?

4. Is this headline completely “true”/accurate or is it based on partially true information/data? Misleading information is often based on partial truths and Reconfigured to suit your purpose. That is, it triggers an emotion, such as anger or fear, and leads to some outcome, such as a like, donation, purchase, sign-up, or vote.

5. Are the headlines themselves free of embedded logical fallacies, especially those that make straw-man arguments, emotional appeals, or are intended to polarize, rally, or otherwise “draw in” readers? Is there any harsh language used?

6. Is the topic behind the headline important? Is it worth understanding more deeply?

7. Who do you think will benefit if this is accepted as “truth”?

8. Is this information, angle, or “interpretation” new, or has it been said before (and fact-checked or debunked)?

9. Is the headline-specific data (fact-based) or position (opinion-based) shared by other reputable publishers or contrasted with the “status quo”? If the latter, how does it affect the headline?

10. What background information do I need to assess its credibility? Where can I get more information about a headline’s topic to better assess its credibility? What would I gain or lose if I accepted it as such?

11. Do “news articles” accurately represent the “big picture” or are they “selected” (in or out of context) designed to provoke an emotional response in the reader?

The second set of questions for thinking critically about news headlines focuses on the News Literacy Project. This is a media standards project that created a series of questions to help students think critically about news headlines.

12. Measure your emotional responses. Is it strong? are you angry? Do you really want that information to turn out to be true or false?

13. Reflect on how you encountered this. Was it advertised on your website? Did it show up on your social media feed? Was it sent to you by someone you know?

14. Consider your headline or message.

a. Are you using excessive punctuation or all caps for emphasis?

b.Does it claim to contain secrets or that the “media” is telling you something they don’t want you to know?

c. Don’t stop at just the headline. Keep exploring!

15. Is this information designed to be easily shared, like a meme?

16. Consider your sources.

a. Is it a famous source?

b. Does this work have a byline (author’s name)? Does the author have any special expertise or experience?

c. Go to the About section of the website. Does this site call itself a “fantasy news” or “satire news” site? Did you notice anything else or not?

17. Are the samples you are evaluating dated?

18. Does this example cite a variety of sources, such as official or expert sources? Will the information in this example appear in reports from (other) news outlets?

19. Do the examples have hyperlinks to other quality sources?

20. Can you use reverse image search to ensure that the images in the examples are authentic (i.e., not modified or taken from another context)?

21. If I search for this example on a fact-checking site like snopes.com, factcheck.org, or politifact.com, is there a fact-check that would label it as untrue?

Remember:

It’s easy to clone an existing website or create fake tweets to fool people. AI and “deepfakes” are becoming increasingly common. Bots operate on social media and are designed to dominate conversations and spread propaganda. Propaganda and misinformation often use real images of unrelated events. If you find examples of misinformation, debunk them. That’s good for democracy!

You can download the complete “checkology” PDF here and find additional resources at checkology.org.