Written by Grant Wiggins & The TeachThought Staff

Please admit it. Just by reading the list of six levels of Bloom’s taxonomy, I did not read the entire book explaining each level and the rationale behind the taxonomy. No need to worry. you are not alone. This is true for most educators.

But that efficiency comes at a price. As the errors below demonstrate, many educators have incorrect views about the taxonomy and the levels within it. And perhaps the greatest weakness of the Common Core standards is that, in line with the rationale for the taxonomy, they do not pay special attention to the use of cognitively focused verbs.

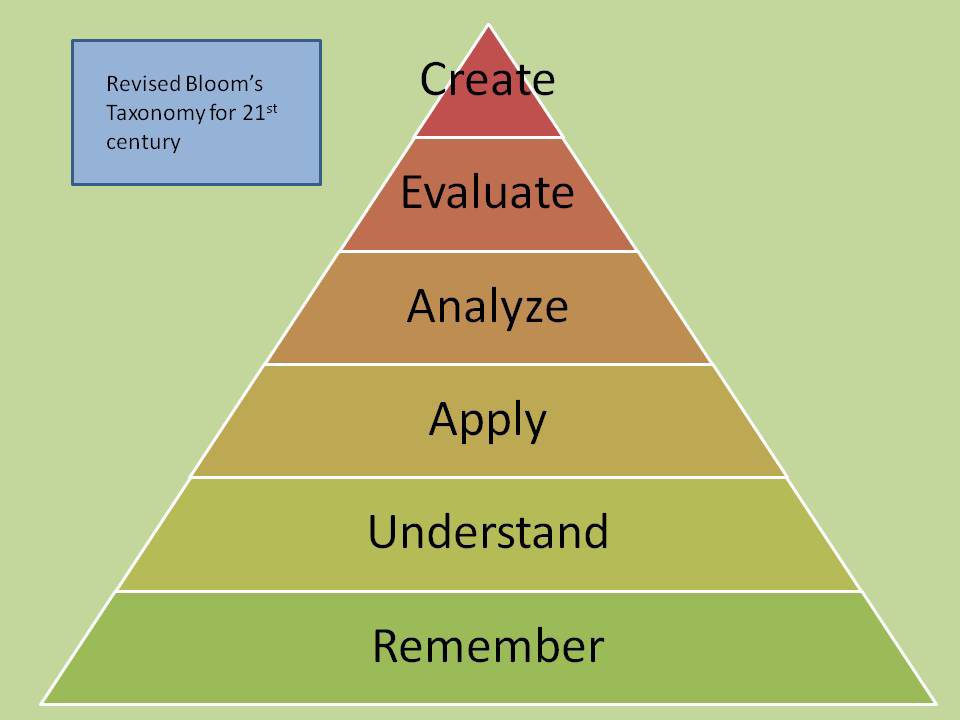

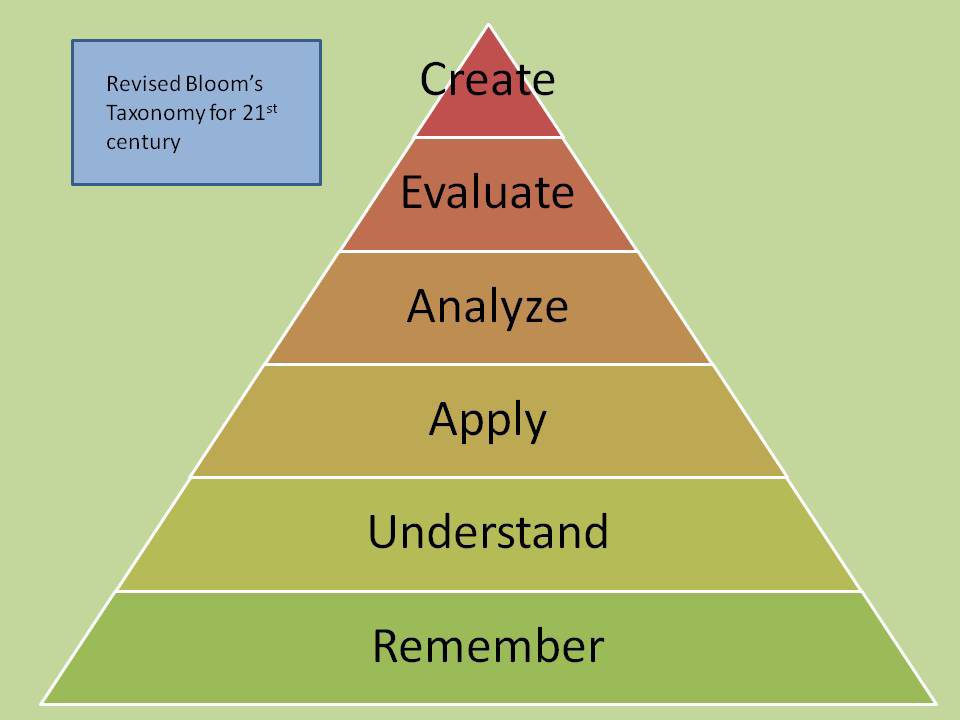

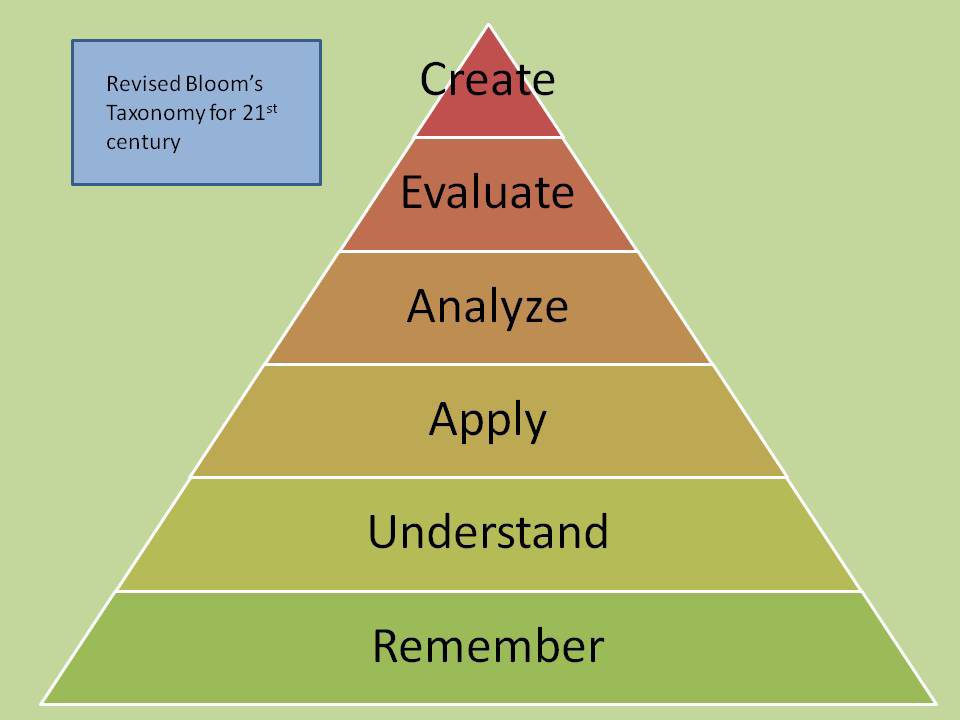

1. The first two or three levels of the taxonomy contain “lower order” thinking, and the last three or four levels contain “higher order” thinking.

This is incorrect. The only sub-goal is ‘knowledge’. This is because the test only requires recall. Moreover, it makes no sense to think that “understanding” (second level) requires only lower-order thinking.

An important action in interpretation is that, given a communication, students are able to identify and understand the main ideas contained within it and their interrelationships. This requires good judgment and attentiveness in reading documents and forming your own thoughts and interpretations. You also need the ability to judge the larger, more general ideas contained in a document, rather than just paraphrasing parts of it. Interpreters also need to be aware of the limits to which they can draw interpretations.

This higher-order thinking (summarizing, main ideas, conditional and careful reasoning, etc.) is a level that half of students do not reach in reading comprehension. By the way, the expressions “lower order” and “higher order” do not appear anywhere in the taxonomy.

2. “Application” requires practical learning.

As the text makes clear, this is not true and is a misreading of the word “apply.” We apply ideas to situations. For example, you understand Newton’s three laws and the writing process, but can you solve new problems related to them without instruction? That’s the application:

The entire cognitive domain of taxonomy is arranged in a hierarchical structure. That is, each classification within a classification requires skills and abilities that are lower in the classification order. Application categories follow this rule in that applying something requires an “understanding” of the method, theory, principle, or abstraction being applied. Teachers often say, “If students really understand something, they can apply it.”

Questions in the Comprehension category require students to understand abstractions well enough to be able to demonstrate their use correctly, especially when asked. However, “application” requires a step beyond that. When presented with a problem that is new to the student, the student applies the appropriate abstraction without being asked which abstraction is correct or shown how to do so in this situation.

Pay attention to important phrases. When presented with a problem that is new to students, they apply appropriate abstractions without being prompted. Therefore, “application” is actually synonymous with “assignment.”

In fact, the authors strongly advocate the primacy of application/transfer of learning.

The fact that most of what we learn is intended to be applied to real-life problem situations demonstrates the importance of applied goals in the general curriculum. Therefore, the effectiveness of most school programs depends on how well they can be applied to situations that students have not encountered in their learning process. Those familiar with educational psychology will recognize that this is a long-standing problem with the transfer of training. Research shows that understanding an abstract concept does not guarantee that the person will be able to apply it correctly. Students also seem to need practice in reconstructing and categorizing situations so that the correct abstractions are applied.

Why UbD? In your application, the problem must be new. Students must determine where their previous learning fits without any prompting or hints from the scaffolded worksheet. And students need to receive training and practice how to deal with non-routine problems. We designed UbD in part backwards from Bloom’s definition of an application.

Regarding instruction that supports the purpose of transference (and different types of transference), the authors soberly point out:

“We also attempted to organize the literature on the growth, retention, and transmission of different types of educational outcomes and behaviors. Here, we find very little relevant research. … claims have been made…but they are rarely supported by research.”

3. All verbs listed at each level of the taxonomy are roughly equivalent. They are synonyms for levels.

No, there are separate sublevels of classification, and each sublevel increases in cognitive difficulty.

For example, in ‘knowledge’, the lowest level of knowledge is knowledge of terms, the more demanding form of recall is knowledge of the main ideas, schemes, and patterns in the field of study, and the highest level of knowledge is knowledge of theory. It’s knowledge. and structure (e.g., knowing the structure and organization of parliament.)

Comprehension has three sublevels in order of difficulty: Translation, Interpretation, and Extrapolation. For example, key ideas in literacy are classified as interpretive because, as noted above, they require more than “translating” a text into one’s own words.

4. This taxonomy recommends against the goal of “understanding” in education.

It’s just that the word “understand” is too broad. Rather, taxonomies help us more clearly delineate the different levels of understanding we seek.

Returning to the example of the term “understand,” a teacher might use a taxonomy to determine which of several meanings is intended. If that means that the student…is aware of a situation…and describes it in slightly different terms than those originally used to describe it, this falls under the classification category ‘translation’. (this is a lower level of understanding). Deeper understanding is reflected in the next higher level of the taxonomy, Interpretation, where students are expected to summarize and explain…and which teachers can use to further ‘demonstrate understanding’. There are also other levels of taxonomy. ”

5. The creators of the taxonomy believed that it was a valid and complete taxonomy.

No, it wasn’t. They point out that:

“Our attempt to arrange educational behaviors from simple to complex is based on the idea that certain simple behaviors may be integrated with other equally simple behaviors to form more complex behaviors. It was based on the idea that…our evidence on this is not entirely satisfactory, but there is an undeniable fact that the trend indicates a stratification of behavior.

They were particularly concerned that there was no single theory of learning and achievement.

“We described the various behaviors expressed in the educational objectives that we tried to classify. We had to reluctantly agree with Hilgard. Each learning theory is very What is needed is a comprehensive theory of learning on a larger scale than currently appears available.

Subsequent schemas such as Webb’s Depth of Knowledge and the revised taxonomy cannot resolve this fundamental problem, which affects all modern standards documents.

why is this important

Perhaps the biggest failure of the Common Core Standards is that the use of verbs within the standards was arbitrary/careless and overlooked these issues.

There appears to have been no attempt to be precise and consistent in the use of verbs within the standard, so that users do not understand the level of rigor prescribed by the standard and therefore the level of rigor required in local assessments. It has become almost impossible to do so. (None of the documents say how intentional these verb choices were, but previous experience in New Jersey and Delaware suggests that the verbs are used haphazardly.) I know. In fact, the writing team starts changing verbs just to avoid repetition.)

Problems have already surfaced. In many schools, evaluations are not as rigorous as clearly required by standards and mock exams. No wonder the score is low. I’ll discuss this issue in more detail in a later post, but my previous post on standards provides further background on the issue we’re facing.

Update: People are already arguing with me on Twitter as if they agree with everything I’ve said here. Nowhere is it said that Bloom was right about taxonomy. (His doubts about his own work suggest my real views, don’t they?) I’m simply reporting what he said and what is commonly misunderstood. In fact, I am rereading Bloom as part of my taxonomy critique in support of the revised third edition of UbD. This requires a more sophisticated view of the idea of depth and rigor in learning and assessment than currently exists.

This article first appeared on Grant’s personal blog. You can find Grant on Twitter here. 5 common misconceptions about Bloom’s taxonomy. Image attribution flickr user langwitches