The online search behavior of nearly half a million people in 50 countries reveals how mood, education level, gender, background, and culture influence how we satisfy our curiosity and seek new knowledge. sheds new light on how it affects people. So we ask: Are you a hunter, a busy person, or a newly identified “dancer”?

Many of us spend hours following Wikipedia links, some following more or less linear questions, others jumping wildly from topic to topic, and still others following a more or less linear question. is a mixture of both. A collaborative team of scientists has discovered that our browsing patterns include: There are personal fingerprints.

A 2020 formative study in which researchers at the University of Pennsylvania (University of Pennsylvania) assessed the 15-minute Wikipedia browsing habits of 149 participants over a three-week period found that information seekers fall into two categories: busy people and hunters. It became clear that there was a type.

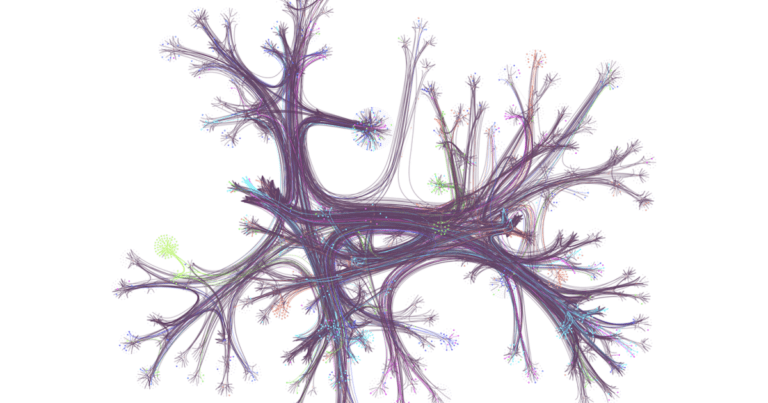

Melissa Pappas/University of Pennsylvania

This new study significantly expands on previous research, analyzing 482,760 people in 50 countries who use Wikipedia on their smartphones, and finds that these two types dominate around the world, as well as new categories. Scientists have confirmed that “dancers” exist.

“Busy people love novelty of all kinds and are happy to jump from here to there, seemingly without any rhyme or reason. This is in contrast to ‘hunters,’ who are more goal-oriented and focused. It’s a target. We’re trying to solve problems, find missing pieces, fill in models of the world,” said Dani Bassett of Pennsylvania.

As Bassett et al. state in their study: “Busy people seek loose threads of novelty, hunters pursue specific answers in projectile paths, and dancers typically work in silos. These three architectural styles emphasize a dimensional approach to the study of curiosity that foregrounds the practice of curiosity as an individual difference. ”

What, then, is this other than the fact that some of our rabbit holes resemble “tunnels” of complex, expansive quests with more side quests than an open-world video game? Can we tell you? Through a systematic analysis, researchers found that countries with higher overall levels of education and greater gender equality compared to regions with more severe social inequalities. We found significant differences in browsing patterns. And this could help us better design learning tools that best suit how different people approach knowledge gathering in different parts of the world.

“We observed that people tend to browse with more focused intent, especially in countries with high inequalities regarding gender and access to education,” said lead author Dale Zhou. “In contrast, in more equal countries, browsing is more extensive, with a wider diversity and topics.

“The exact reasons why this is happening are not entirely clear, but we have some strong hunches, and these discoveries are a sign that scientists in our field will We believe this will prove useful in helping us better understand the nature of curiosity across different cultures and locations.”

The countries or regions assessed are: Algeria, Argentina, Australia, Austria, Bangladesh, Belgium, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Colombia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Ghana, Greece, Hong Kong, Hungary, India, Indonesia, It was Ireland. , Israel, Italy, Japan, Kenya, South Korea, Malaysia, Mexico, Morocco, Nepal, Netherlands, New Zealand, Nigeria, Norway, Peru, Philippines, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Serbia, South Africa, Spain, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Switzerland, Taiwan , Ukraine, UK, USA.

Across this vast field, the Wikipedia phone app was read in 14 different languages.

To reduce bias, 482,760 participants (the “naturalistic dataset”) were selected from a larger pool of over 2 million Wikipedia users. Because what they view may best correlate with the 2020 study’s observations. The researchers determined that “the number of articles visited, the number of unique articles visited, the number of days used per month, and the percentage of articles accessed via Wikipedia hyperlinks (as opposed to from external websites).” We identified a naturalistic dataset by considering the following: ”

Unlike the controlled study conducted at the University of Pennsylvania, participants in the naturalistic dataset had no prior knowledge of the assessment and therefore had different habits. In general, 482,760 people read fewer articles, clicked fewer unique pages, visited fewer internal Wikipedia links, and took fewer days. Through a statistical method known as propensity score matching, the researchers were able to match the 2020 study participants (the “treated” subjects) with the observational data (the “untreated” subjects).

What they were able to form was a network of knowledge diagrammed like a neural network, illustrating the difference between the narrow and loose thematic connections representing the hunter and the busybody. The survey confirmed the presence of a “dancer” type as well as a country-wide browse that falls into the categories of hunters and busybodies. This was thought to exist but had not been estimated in previous studies.

“Dancers are flow-driven people, but unlike busy people, they jump between ideas in creative, choreographed ways,” said study co-author Perry Zahn, professor of philosophy at American University. says. “They don’t just randomly jump. They connect different domains and create something new.”

This browsing style is different from hunters and busy people. Dancers weave paths through new information across a wide range of subjects that have some tangible connection.

“It’s less about randomness and more about finding connections that other people don’t notice,” Bassett says.

The study identified specific areas of interest across languages and countries. Busy people were more likely to read articles about cultural topics such as media, food, art, philosophy, and religion. Hunters were more likely to read pages that covered science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).

“Hunters were more likely to read historical and social articles in some languages (German and English), while nosy people were more likely to read historical and social articles in some languages (Arabic, Bengali, Hindi, Dutch, Chinese). ),” the researchers noted. “These trends are consistent with the hypothesis that busy people are more drawn to social topics than hunters.”

Looking at browsing habits in relation to population-wide indicators of education, mood, well-being, and gender equality, the researchers came up with three hypotheses as to why meddlers and hunters predominate in different regions.

“One is that countries with more severe inequality may have more patriarchal structures of oppression, constraining their approach to knowledge production to be more hunter-like. ” Bassett said. “In contrast, more egalitarian countries are more accepting of diverse ideas and therefore more diverse in their ways of engaging with the world. It’s similar to someone who does.

A second reason, they suggest, is that knowledge seekers use Wikipedia for different purposes in different countries. For example, users in wealthy countries may be visiting the site for entertainment and leisure rather than work. And finally, apparent differences may be due to differences in national age, gender, socio-economic status, and education.

Overall, the team highlights how an individual’s curiosity and quest for knowledge depends on many broad factors, and how little we know about what influences our browsing habits. It shows.

“What this tells us is that people, and perhaps children, have different curiosity styles that can influence how they approach learning,” Bassett said. “Children with hunter-like curiosity may struggle if they are evaluated in a way that favors a nosy style, and vice versa. Understanding these styles can improve the educational experience. It may help you adjust and better support your individual learning path.

“One question I’m particularly interested in is whether people browse differently at different times of the day. Maybe they’re more hunters in the morning and nosy at night? “No,” Bassett says.

Naturally, this comprehensive study opens the door to many specific population studies and, of course, how artificial intelligence systems learn.

“This opens up new avenues of research, including the role of biological processes in shaping how we seek information,” said Shubhankar Patankar, a doctoral student in the Pennsylvania School of Engineering. said. “Injecting the concept of curiosity into AI systems that learn from interactions is an increasingly important area of research,” says Patankar.

Incidentally, ad-free Wikipedia is at the heart of both studies, as it is considered a reliable model for investigating how we satisfy our curiosities online.

“Wikipedia is a very special place on the internet,” said study author David Lydon Staley, an assistant professor at the Annenberg School for Communication who led the 2020 basic research. “This site contains only free content and no commercial advertising. Much of the rest of the modern digital environment is designed to activate individual buying impulses and customize media content. This raises questions about the extent to which we are responsible for where our curiosity takes us in online contexts beyond Wikipedia.

The study was published in the journal Science Advances.

Source: University of Pennsylvania