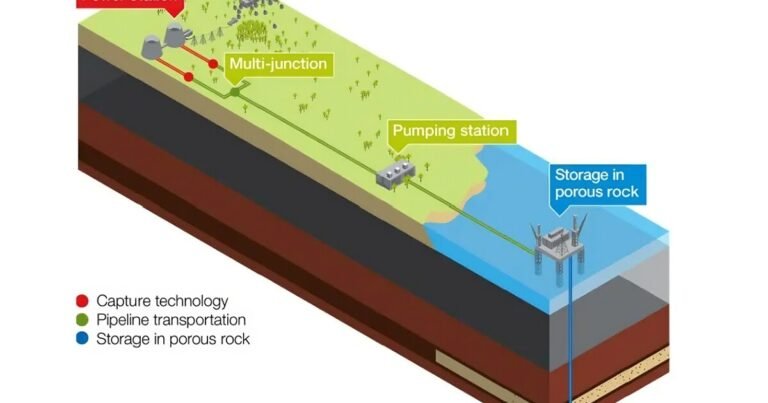

ExxonMobil just signed a lease for 271,068 acres of subsea land off the coast of Galveston, Texas, to capture carbon emissions (CO2) and permanently inject it into underwater rock, making it the first company in the short history of the U.S. It will become the largest CO2 disposal site.

All lease proceeds, amounting to millions of dollars, will go toward the Texas Permanent School Fund, which was established in 1845 to support public schools and education to reduce the need for borrowing from the state. As of August 31, 2024, the Fund had a balance of USD 56.8 billion.

In 1986, a volcanic crater lake called Lake Nyos in Cameroon, Africa, experienced a lacustrine eruption, also known as the “lake overturn.”

Over time, CO2 from the underground magma seeped into the deep lake water. Normally, the pressure keeps the CO2 dissolved in the water, but for some reason, such as a landslide or a change in temperature or pressure, the CO2 suddenly begins to degas and rush to the surface, raising the lake to a height of 79 feet ( 79 feet). The tsunami (24 meters) caused carbon dioxide to flow into the valley.

Jack Lockwood, USGS

About 1.6 million tonnes (1.45 tonnes) of CO2 was released in a 15.5 mile (25 km) radius, suffocating about 1,700 people and 3,000 livestock in four villages that settled in the evening. Since CO2 is heavier than air, it flowed quickly along the valley floor.

The damage was done within minutes, leaving only a few survivors. After several hours, the carbon dioxide dissipated, ending one of the deadliest natural gas release events in history.

Wikipedia Creative Commons

Why is carbon capture and storage (CCS) different from Lake Nyos, and how safe is it?

Most of us are familiar with hydraulic fracturing (fracking), which extracts crude oil and natural gas from the earth’s crust, but some of these fracture sites are also recycled into CCS in a process called enhanced oil recovery (EOR). What is happening is not well known. It’s rare, but it does exist.

For example, the Weyburn Middale project in Canada uses the EOR method, which involves injecting CO2 into a hydraulic fracturing site to extract the last bits of black gold, leaving the CO2 (hopefully) permanently trapped underground. – More than 33 million tonnes (30 million tonnes) (1 million tonnes) have been stored since 2000.

Texas also has an EOR site. The Petra Nova CCS project is located in Jackson County, just southwest of Houston.

More generally, CCS sites are intentionally planned and designed for CO2 storage.

Norway has been a pioneer in carbon capture and storage with projects such as the Sleipner project in the North Sea and the Snovit field in the Barents Sea. Since the start of operation, there have been no reports of serious accidents or leaks.

The Sleipner project began in 1996 and became the world’s first industrial-scale CCS project. It will store approximately 1 million tons of CO2 per year and inject it into the Utsila Formation, a highly porous sandstone formation located approximately 2,625 feet (800 m) below the ocean floor.

exxon mobil

The Snøhvit field was started in 2008 and captures approximately 700,000 tons of CO2 per year, injecting the captured carbon even deeper, 8,530 feet (2,600 m) below the ocean floor. Both locations are sealed with an impermeable “cap-lock” layer to prevent CO2 from escaping.

Typically, CO2 is injected more than 1 km (3,280 feet) below the ocean floor, where temperature and pressure keep it in a supercritical state. This means the gas behaves more like a liquid, which helps it get trapped underground. Just as CO2 becomes dry ice when cooled to -109.3°F (-78.5°C), it becomes a liquid at approximately 88°F (31°C) under a pressure of 1,070 psi (73.8 bar). There is also.

If a leak occurs at a storage site, the CO2 acidifies the surrounding waters and negatively impacts nearby marine life.

In theory, this type of CCS site could safely store CO2 waste for millions of years, barring a world-ending catastrophe, such as an Earth-destroying asteroid. In that case, CO2 leakage may be the least of our worries.

Source: Exxon Mobile